The Secret Surrender: How the ‘I Can’t’ vs ‘I Won’t’ Framework Keeps You Comfortable, Broke, and Defenseless

A 12-year case study in strategic surrender, the hidden architecture of avoidance, and the Extreme Ownership doctrine that replaces it.

You stop having to defend territory. You stop having to make strategic decisions. You stop carrying the terrible weight of agency.

And if you’re clever about it, you can surrender in a way that looks like you’re still fighting.

I know this because I lived it for years.

I built an entire life around strategic surrender. I did it so skillfully that I convinced myself I was actually trying. I had all the external markers of effort—the long hours, the stress, the constant motion.

What I didn’t have was any real skin in the game.

Because the moment you have something worth defending, you can be evaluated. You can fail visibly. You can be found wanting.

And I had discovered something far more seductive than success: the psychological comfort of having nothing left to defend.

Part I: The Fortress of Defenselessness

The Strategic Surrender Doctrine

Strategic surrender is not giving up. That would be too honest, too visible.

Strategic surrender is the psychological operation where you trade agency for the comfort of not being responsible for outcomes. It’s the quiet abdication of power disguised as prudence, realism, or self-awareness.

The transaction is elegant in its simplicity: You convince yourself you “can’t” instead of admitting you “won’t.” This single linguistic trick purchases protection from judgment, evaluation, and the existential terror of being tested and found insufficient.

This is different from a tactical retreat.

When a general pulls back from a battle to preserve his force for a more advantageous engagement, he maintains agency. He’s choosing the terms of future combat.

Strategic surrender, by contrast, is the decision to stop engaging entirely while maintaining the fiction that you’re still a player.

It’s also different from genuine limitation.

If you’re five-foot-seven, you can’t play center in the NBA. That’s reality. But “I can’t compete for that promotion” when you’re qualified? That’s not limitation. That’s choice masquerading as constraint.

I know the difference intimately because I lived inside the con for years.

Here’s what that looked like:

There was a promotion cycle at the bank where I worked. I was qualified—more than qualified. I had the experience, the performance record, the relationships. But I didn’t apply.

The story I told myself was sophisticated: “The competition is too intense. These other candidates have been positioning for this for months. I can’t compete at that level.”

The actual truth was simpler and more pathetic: I won’t risk being evaluated and found wanting.

“Strategic surrender is the quiet abdication of power disguised as prudence, realism, or self-awareness.”

Because here’s what I understood at a level deeper than conscious thought: If I applied and didn’t get the promotion, I would have to defend that failure. I would have to explain it to myself, to my family, to my colleagues. I would have visible proof of my insufficiency.

But if I never applied? If I convinced myself and everyone else that I “couldn’t” compete? Then there was nothing to defend. The failure became invisible, absorbed into the background radiation of my life rather than standing out as a discrete, identifiable defeat.

This is the genius of strategic surrender: It makes failure impossible to pin on you because you never claimed to be playing the game.

And it worked. I felt relieved. Safe. Protected.

I also stayed at that bank through three rounds of staff cuts, deteriorating working conditions, and a slow erosion of any meaningful impact I could have. I watched my more aggressive colleagues ascend while I told myself stories about sustainability and work-life balance.

The fortress of defenselessness is comfortable. It’s also a prison.

The Imposter Syndrome Shield

Imposter syndrome gets treated like an unfortunate psychological affliction—something that happens to talented people who just can’t see their own worth. That’s the therapeutic framing (Clance & Imes, 1978).

Here’s the operational reality: Imposter syndrome is a weapon. It’s the perfect defensive armament for someone engaged in strategic surrender.

The logic is airtight: If I don’t spend energy, time, or capital pursuing the goal, I can’t fail at the goal. The fear of being exposed as a fraud becomes the justification for never putting yourself in a position where exposure is possible.

I used this weapon with surgical precision for years.

Every significant opportunity that came my way triggered the same sequence:

Initial excitement

Creeping sensation that I wasn’t actually qualified

Recognition that pursuing this would require evaluation by people who would discover my inadequacy

Strategic withdrawal disguised as realism

The self-talk sounded like this:

“I don’t have the background for this.”

“I haven’t put in the preparation time.”

“Other candidates are more naturally suited.”

“I wouldn’t be able to deliver at the level they’d expect.”

Every one of these statements sounded reasonable. Humble, even. Self-aware.

Every one of them was a lie in service of surrender.

The psychological payoff structure was perfect. By not investing real resources in the pursuit, I guaranteed I wouldn’t experience the specific failure I feared. The self-fulfilling prophecy loop closed seamlessly:

Fear of being exposed as inadequate → Strategic withdrawal from situations requiring evaluation → Guaranteed non-achievement in those domains → Confirmation that I was right to be afraid → Reinforced fear of exposure

The system fed itself. And because I never actually tested the hypothesis—never spent the energy, made the investment, took the risk—I never generated evidence that could break the loop.

“Imposter syndrome is a weapon. It’s the perfect defensive armament for someone engaged in strategic surrender.”

Here’s what makes this particularly insidious: This isn’t about lacking confidence. I had plenty of confidence in domains where I felt safe. I could operate at a high level in my comfort zone. I could be the calm, unflappable professional everyone relied on.

What I lacked was the willingness to subject that self-image to a real test in a domain where failure was possible.

Because confidence is cheap when you’re operating in safe territory. What I was protecting wasn’t my actual capabilities—it was my fragile, untested self-image. The internal narrative that said “I’m capable, I just haven’t chosen to pursue X yet.”

Imposter syndrome allowed me to keep that narrative intact. As long as I never really tried, I never had to discover whether the narrative was true.

The cruel mathematics of this approach became clear only in retrospect: Every year I spent protecting my self-image from testing was a year I didn’t develop actual capabilities. The gap between who I told myself I could be and who I actually was widened with every strategic surrender.

But I didn’t feel that widening. What I felt was safe.

The imposter syndrome shield worked exactly as designed. It protected me from evaluation, from visible failure, from the terrible discomfort of being found insufficient.

It also protected me from growth, achievement, and any form of success that required me to defend a position I’d claimed.

The Hidden Architecture of Avoidance

Strategic surrender doesn’t happen accidentally. It requires architecture—psychological infrastructure that supports the entire operation.

I built mine carefully over years, though I didn’t recognize it as construction at the time. I thought I was being strategic. Thoughtful. Careful.

I was building a fortress of justifications.

The architecture had three load-bearing walls:

Wall One: The Narrative of Reasonableness

Every surrender needed a story that sounded rational. Not just to others—to myself. The story had to be sophisticated enough that I could believe it while simultaneously knowing, at some deeper level, that it was a lie.

“I’m being realistic about my current capacity.”

“I’m prioritizing sustainability over short-term gains.”

“I’m waiting for the right opportunity rather than forcing it.”

These stories did double duty: They explained my inaction to others while protecting me from my own judgment.

Wall Two: The Metrics of Motion

I needed proof that I was trying. So I generated metrics—hours worked, tasks completed, problems solved. The metrics created the appearance of progress while measuring nothing that actually mattered.

I tracked my productivity on low-stakes tasks with religious devotion. I optimized my workflow for maximum efficiency on work that carried minimum risk. I created systems for managing systems.

The motion was real. The distance covered was zero.

Wall Three: The Comparative Comfort

Every time I felt the pull toward something significant, I reminded myself how much worse things could be.

“At least I have a stable job.”

“At least I’m not in debt like some people.” (This was before the bankruptcy.)

“At least I’m not burning out like those guys who are always chasing the next thing.”

The comparative comfort was a sedative. It kept me from recognizing that “better than the worst-case scenario” is not the same as “good.”

“The fortress of defenselessness requires constant maintenance. Each surrender must be justified, each avoided risk must be explained, each unchosen path must be dismissed as unsuitable.”

The fortress of defenselessness requires constant maintenance. Each surrender must be justified. Each avoided risk must be explained. Each unchosen path must be dismissed as unsuitable.

I spent enormous energy maintaining this architecture. Energy that could have gone toward actually building something worth defending.

But the architecture served its purpose: It made surrender feel like strategy.

And for years, that was enough.

Part II: The Hidden Payoff Structure

The Comfort of Having Nothing to Defend

Let’s talk about what “I can’t” actually purchases. Because this isn’t irrational behavior—it’s a transaction. And like any transaction, you have to understand what both parties are getting.

What I received in exchange for my agency:

Freedom from evaluation. When you don’t claim territory, nobody can evaluate your defense of it. You’re not in the game, which means you can’t be judged by the game’s standards. This is intoxicating if you’ve built your identity around avoiding criticism.

Protection from visible failure. Failure still happens—you still don’t get the promotion, the opportunity, the outcome. But it’s ambient failure, diffuse and deniable. “I never really wanted that anyway.” “That wasn’t the right fit.” “I was being strategic about where to invest my energy.” The failure has nowhere to attach because you never planted your flag.

The moral high ground of victimhood. This is the most seductive element of the whole package. When you surrender strategically, you get to be the person things happen to rather than the person who makes things happen. And in our current cultural moment, that’s a position of moral superiority. You’re not responsible for your outcomes because the system, the competition, the circumstances made it impossible. You’re a victim of external forces, which means you’re innocent.

Permission to avoid uncomfortable growth. Growth requires exposing your current inadequacy. You have to suck at something before you get good at it. Strategic surrender short-circuits this entirely. You never have to experience the specific discomfort of being a beginner, of being evaluated while incompetent, of the gap between your current performance and the standard you’re pursuing.

This is the covert contract with mediocrity: “If I don’t claim agency, no one can hold me responsible for my life’s outcomes.”

I lived inside this contract for years. And it felt like wisdom.

The Nice Guy operating system—the psychological framework I inherited from childhood—made this transaction feel not just reasonable but necessary. Because Nice Guys don’t make waves. They don’t create conflict. They don’t put themselves in positions where they might have to defend their choices against criticism.

“Strategic surrender doesn’t protect you from judgment. It just ensures the judgment will be accurate and devastating.”

And what requires more defense than ambition? Than claiming you deserve something? Than putting your name on a piece of work and saying “I made this, evaluate it”?

So I optimized for defensibility. Every decision ran through the same filter: “Can I defend this if it goes wrong?” And the only truly defensible position is the one where you never claimed to be trying in the first place.

The sovereignty paradox became clear only after I’d paid its full price: The more you surrender to avoid judgment, the more you guarantee the judgment will be correct.

Because here’s what I didn’t understand while I was inside the system: People were evaluating me anyway. My colleagues, my friends, my own nervous system. The judgment I was trying to avoid by not claiming territory? It was happening regardless—except now the judgment was about my passivity, my risk-aversion, my perpetual motion that never actually covered distance.

Strategic surrender doesn’t protect you from judgment. It just ensures the judgment will be accurate and devastating.

The Theater of Frantic Effort

Here’s where strategic surrender reveals its true genius: It doesn’t look like surrender at all. It looks like hustle.

I mastered the theater of frantic effort. I was always moving, always busy, always stressed about something. I would obsess over minor decisions, overthink trivial matters, create elaborate systems for managing tasks that didn’t matter.

I called these my “super hustle moments”—periods where I was working constantly, staying late, thinking about work during every waking moment. I wore my stress like a badge of honor.

Look how hard I’m trying. Look how much I care. Look at all this effort I’m expending.

What I wasn’t doing: Making any decisions that carried real risk.

The busy-work served multiple functions simultaneously:

It created the appearance of engagement. Nobody could accuse me of not trying—I was visibly exhausted from all the trying.

It generated legitimate stress and fatigue, which became their own justification. “I’m doing everything I can” felt true because I was genuinely tired. The fact that I was tired from obsessing over low-stakes tactical execution rather than making high-stakes strategic decisions was a detail I didn’t examine.

It consumed the time and energy that might otherwise have gone toward actual risk-taking. You can’t pursue the big scary opportunity if you’re buried in managing the small safe tasks. The busy-work was a prophylactic against agency.

It created social proof of effort. When my friends or coworkers asked why I wasn’t pursuing certain opportunities, I had an ironclad defense: “I’m already overwhelmed with what I’m doing.” True statement. Completely irrelevant to the actual question of strategic priority.

This is the difference between real effort and theater effort:

Real effort is strategic. It’s directed at high-leverage outcomes. It creates actual risk because you’re investing resources in something that might fail. It requires you to choose, which means accepting what you’re not choosing. It’s often calmer than theater effort because it’s focused rather than frantic.

Theater effort is tactical. It’s directed at safe busy-work. It creates the appearance of risk while remaining fundamentally safe because nothing you’re doing actually matters enough to fail at. It requires you to avoid choosing by doing everything at a superficial level. It’s characterized by stress and motion because that’s the point—the stress proves you’re trying.

I confused the two for years. I genuinely believed that my constant motion, my perpetual stress, my exhaustive attention to detail on minor matters constituted real work toward meaningful goals.

It didn’t. It was defense. The frantic effort was itself a form of strategic surrender—working hard on safe things to avoid working smart on scary things.

“Real effort toward meaningful goals creates the possibility of victory. Theater effort creates defensible exhaustion.”

Here’s the tell: Real effort toward meaningful goals creates the possibility of victory. Theater effort creates defensible exhaustion.

I generated years of defensible exhaustion. I could always explain why I hadn’t pursued the big opportunity, made the significant move, taken the real risk: “I’m already doing everything I can possibly do.”

What I was actually doing: Everything I could possibly do that wouldn’t require me to defend a position I’d claimed.

The theater was convincing. I convinced my friends, my colleagues, most importantly myself.

The audience was captivated. The show ran for years.

And while I was performing, the opportunities I was afraid to pursue went to people who understood the difference between motion and progress.

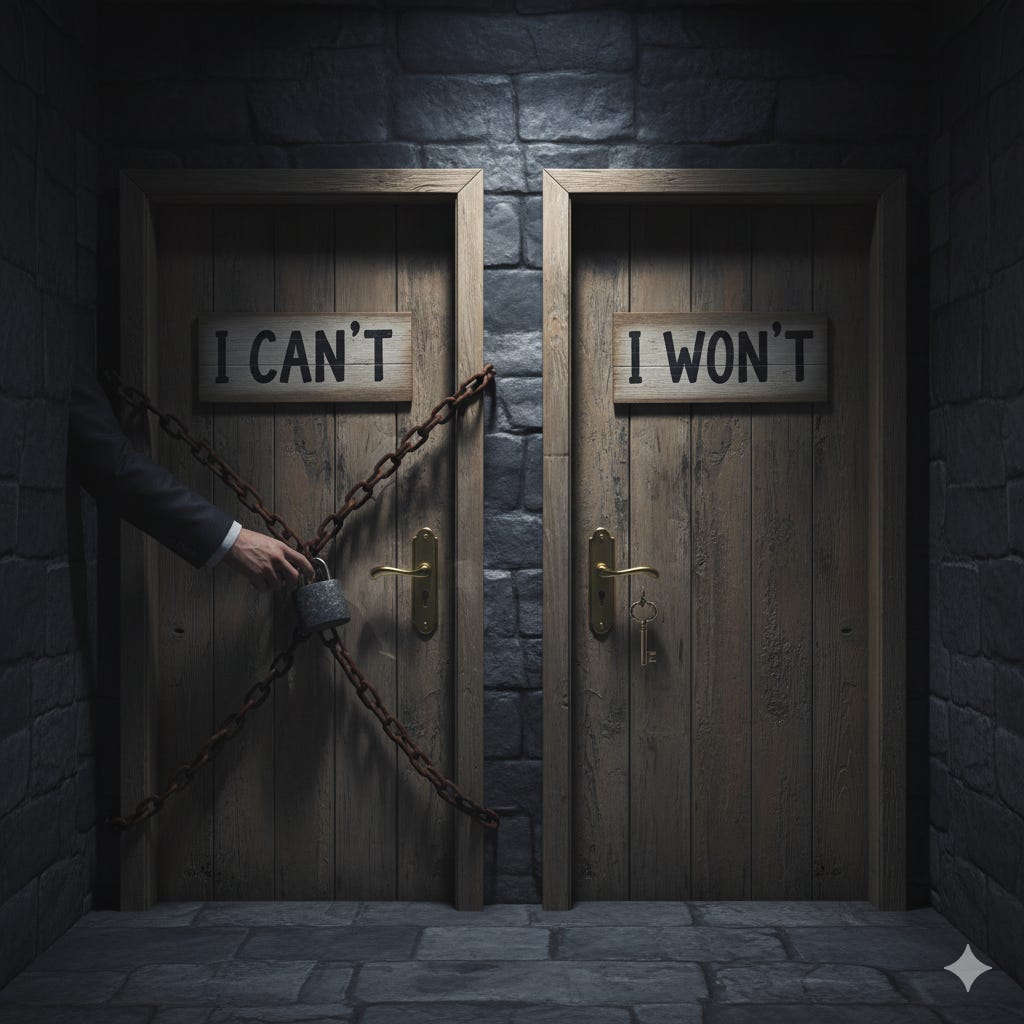

The “I Can’t” vs. “I Won’t” Linguistic Con

Language is a psychological weapon. And the most devastating weapon in the strategic surrender arsenal is the phrase “I can’t.”

These two words accomplish something extraordinary: They shift an internal choice to an external constraint. They transform an act of will into a fact of nature.

“I can’t” implies there’s a force outside your control preventing the action. It removes you from the equation. You’re not choosing—you’re subject to circumstances beyond your agency.

“I won’t” acknowledges the choice. It requires you to own the decision, which means you have to justify it—to others, to yourself, to the part of your nervous system that knows the difference between genuine limitation and strategic retreat.

Your body knows the difference even when your mind lies.

I deployed “I can’t” with surgical precision for years:

“I can’t compete for that promotion” actually meant “I won’t risk being evaluated and found wanting.”

“I can’t leave this deteriorating situation at the bank” actually meant “I won’t face the uncertainty of something new and the possibility I might fail at it.”

“I can’t invest in building my own business” actually meant “I won’t prioritize long-term sovereignty over short-term psychological comfort.”

“I can’t afford to take that risk” actually meant “I won’t tolerate the discomfort of exposing my current financial, psychological, and social position to potential loss.”

“I can’t pursue that opportunity right now” actually meant “I won’t put myself in a position where I might have to defend my performance against a meaningful standard.”

Every “I can’t” was a “I won’t” in disguise. And the disguise served a critical function: The disguise served a critical function: It protected my self-image from the intense pain of what Dr. William Dodson calls Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria.

“Every ‘I can’t’ was a ‘I won’t’ in disguise. And the disguise served a critical function: It protected my self-image.”

Because “I can’t” lets you maintain the fantasy that you would succeed if only circumstances were different. You’re still capable, still talented, still positioned for eventual victory—you’re just constrained by forces beyond your control right now.

“I won’t” forces you to confront the choice. And once you acknowledge the choice, you have to answer the question: Why are you choosing this?

The honest answer—”Because I’m afraid of being evaluated and found insufficient”—destroys the whole psychological edifice. It reveals the strategic surrender for what it is.

So I didn’t use “I won’t.” I used “I can’t” religiously, reflexively, automatically.

I can’t compete with those candidates.

I can’t make a move right now with our financial situation.

I can’t risk changing industries at this stage.

I can’t pursue that without more preparation.

Every one of these statements sounded reasonable. Every one of them was a lie.

The linguistic con worked perfectly until I learned to translate my own language. Until I started hearing “I won’t” underneath every “I can’t.”

Once you hear it, you can’t unhear it.

“I can’t afford to take time off to pursue that certification.”

Translation: “I won’t prioritize an investment in my capabilities over maintaining my current comfort level.”

“I can’t compete with people who’ve been positioning for this for years.”

Translation: “I won’t enter a competition where I might lose visibly.”

“I can’t pursue that opportunity—I don’t have the right background.”

Translation: “I won’t subject my current self-image to a test that might reveal its inaccuracy.”

The shift from “I can’t” to “I won’t” is more than semantic. It’s the difference between being a passive victim of circumstance and an active architect of your own limitation.

And once you make that shift, the fortress of defenselessness becomes uninhabitable.

Because you can live with “I can’t.” It’s not your fault. Circumstances conspired against you.

You cannot live with “I won’t” and maintain your self-respect. Not once you see it clearly.

The con worked for years. It purchased temporary psychological comfort.

The bill came due with interest: kidney disease, bankruptcy, and a decade of potential I refused to pursue because pursuing it would have required me to defend something.

Part III: The Recognition Protocol

The Moment of Seeing Through the Con

The spell breaks in stages, not all at once.

For me, it started with a recognition I didn’t want to have: I was succeeding in areas I wasn’t defending.

The relationships where I operated without defensive theater were my strengths. Friends trusted my judgment and sought me out when things got difficult. My interactions with women improved dramatically when I stopped trying to manage outcomes and just showed up with the same calm presence I brought to professional crises. I hadn’t achieved this through the frantic hustle I applied to safe work tasks. I’d achieved it through calm, present, undefended engagement.

My professional demeanor—the unflappable calm I brought to crisis situations—was one of my genuine competitive advantages. Colleagues sought me out specifically because I didn’t panic, didn’t create drama, stayed strategic when everyone else went tactical. I hadn’t developed this capability through stress and overthinking. It emerged from something more fundamental in my temperament.

My ability to build systems, see patterns, identify leverage points—these were real skills that had generated real results in domains where I’d allowed myself to operate.

The common thread: These were all areas where I wasn’t trying to defend a claimed position. I wasn’t performing competence; I was simply being competent.

And the results were better.

This created a crack in the whole psychological edifice. If I was succeeding without the stress-hustle, and failing despite the stress-hustle, then the problem wasn’t effort. The problem was where I was directing it.

The primary realization: “I’m more capable than I’ve been admitting.”

The secondary realization, which took longer and hurt more: “The stress-hustle was itself a form of surrender—I was working hard on safe things to avoid working smart on scary things.”

Everything inverted.

The calm competence I displayed in my relationship and in crisis management wasn’t a consolation prize for not pursuing bigger goals. It was evidence of what I could do when I wasn’t consumed by defensive theater.

The frantic effort I’d poured into low-stakes tasks wasn’t proof of commitment. It was proof of avoidance.

The “I can’t compete at that level” story wasn’t humility or realism. It was cowardice dressed in reasonable language.

“I saw it all at once and couldn’t unsee it. The defense mechanisms that had felt like wisdom revealed themselves as elaborate rationalizations for strategic surrender.”

I saw it all at once and couldn’t unsee it.

The defense mechanisms that had felt like wisdom revealed themselves as what they were: elaborate rationalizations for strategic surrender.

And once you see the con, you’re faced with a choice. You can close your eyes, rebuild the story, go back to the comfort of “I can’t.”

Or you can acknowledge what you’ve been doing and decide whether you’re willing to stop.

The Perfectionism Connection

Perfectionism was the weapon I used to enforce strategic surrender at the tactical level.

The logic appeared unassailable: “If I can’t do it perfectly, I won’t do it at all.” This sounds like high standards. It’s actually a guarantee of inaction.

Because perfect is a standard that exists only in the abstract. In execution, there’s only “good enough to achieve the objective” and “insufficient to achieve the objective.” Perfectionism deliberately conflates these categories to create a third option: “Don’t attempt it.”

I wielded this weapon mercilessly against myself.

Every significant opportunity triggered the perfectionism protocol:

Identify the ideal version of how this should be executed

Recognize that you don’t currently have the resources, time, or skills to execute at that level

Conclude that attempting it would be irresponsible—you’d be setting yourself up for failure

Retreat to safe territory

The perfection standard served multiple functions:

It sounded like high standards rather than fear

It created an impossible benchmark that justified non-action

It allowed me to criticize others for not meeting standards I wasn’t subjecting myself to

It protected me from the vulnerability of producing work that could be evaluated

The breakthrough came when I recognized that my actual successes—the relationship, the calm crisis management, the strategic thinking people valued—had never been perfect. They’d been good enough to achieve the objective.

I hadn’t built a strong marriage by being the perfect husband. I’d built it by being present, honest, and willing to own my mistakes when they happened.

I hadn’t become valuable to colleagues by executing flawlessly. I’d become valuable by making sound strategic calls under uncertainty and pressure.

I hadn’t developed my systems-thinking capability through perfect analysis. I’d developed it through iterative refinement of imperfect initial frameworks.

Success in every domain that mattered had come from good-enough execution, not perfect planning.

But I couldn’t apply this understanding to the domains I was afraid of. Because in those domains, perfectionism was the enforcement mechanisfm for surrender.

The shift happened when I encountered the 80/20 principle—Pareto’s observation that 80% of results come from 20% of efforts.

This framework destroyed perfectionism’s credibility.

If 80% of the value comes from 20% of the work, then perfectionism—the obsessive refinement of the final 20% of quality—is a catastrophic misallocation of resources.

More importantly: Perfectionism in planning is often procrastination in execution.

“Perfectionism in planning is often procrastination in execution.”

I had been demanding perfect clarity, perfect preparation, perfect conditions before I would act on significant opportunities. What I was actually doing: Creating an impossible standard that justified perpetual delay.

The new understanding crystallized: Success doesn’t require what I thought it did.

It doesn’t require perfect preparation—it requires sufficient preparation and willingness to learn during execution

It doesn’t require eliminating all risk—it requires identifying acceptable risk and managing it strategically

It doesn’t require stress-hustle on comprehensive analysis—it requires calm focus on high-leverage variables

The old operating system: Perfectionism → Overwhelm → Strategic surrender → “I can’t”

The new operating system: 80/20 → Strategic focus → Calm execution → “I will, on my terms”

But implementing the new OS meant abandoning the comfort of the old one. It meant accepting that I would produce work that wasn’t perfect. That I would be evaluated on that imperfect work. That I might fail visibly.

It meant having something worth defending.

And that was terrifying.

The Self-Awareness Trap

There’s another layer to this that’s worth examining: the way self-awareness itself can become a weapon of strategic surrender.

I prided myself on being self-aware. I could analyze my own psychology with precision. I understood my patterns, recognized my triggers, identified my defense mechanisms.

And I used all that awareness to do exactly nothing.

Self-awareness without action is just spectating on your own life. It’s watching yourself make the same choices, avoid the same risks, surrender to the same fears—except now you have a sophisticated psychological framework to explain why.

I could tell you exactly why I wasn’t pursuing certain opportunities. I could map the childhood origins of my conflict-avoidance. I could explain the Nice Guy operating system in detail. I could describe the perfectionism trap with clinical precision.

What I couldn’t do: Make a different choice.

The self-awareness trap works like this: You mistake understanding for progress. You confuse diagnosis with cure. You feel like you’re doing something productive by analyzing your patterns—when all you’re actually doing is intellectualizing your surrender.

This is particularly seductive for intelligent people. We’re good at analysis. We can build sophisticated models of our own psychology. We can see the patterns, understand the causes, predict the outcomes.

And we can use all that intelligence to avoid the simple, uncomfortable truth: You already know what you need to do. You’re just not willing to do it.

“Self-awareness without action is just spectating on your own life.”

The recognition that broke this trap for me: I didn’t need more insight. I needed more courage.

I didn’t need to understand myself better. I needed to be willing to subject my current self to the discomfort of change.

I didn’t need another framework. I needed to make a choice and own its consequences.

Self-awareness is valuable. But it’s a tool, not a destination. And if you’re using it to explain your inaction rather than inform your action, you’ve turned wisdom into another form of strategic surrender.

Part IV: The True Cost Calculation

What Strategic Surrender Actually Costs

The comprehensive accounting of what I paid for the comfort of having nothing to defend:

Financial devastation. Years of income I didn’t pursue because pursuing it would have required claiming I deserved it. Promotions I didn’t compete for because competition meant risk of visible failure. Strategic career moves I didn’t make because new territory meant new evaluation. The compound effect: bankruptcy, charge-offs, no war chest, no buffer. I purchased psychological comfort and paid for it with financial ruin.

Physical deterioration. The stress I generated through frantic effort on safe tasks had metabolic consequences. Stage 2 chronic kidney disease. Diabetes. Hypertension. The body keeps score even when the mind lies to itself. I was stressing myself into medical crisis over tasks that didn’t matter while avoiding the healthy stress of pursuing goals that did.

Psychological compounding. Shame doesn’t depreciate—it compounds. Every year I spent knowing I was conning myself added to the psychological debt. The gap between who I told myself I could be and who I was actually being widened with each strategic surrender. And underneath it all: the growing certainty that I was a fraud, because I was. I was performing the theater of effort while avoiding actual risk.

Relational costs. My wife never lost respect for me in the domains where I showed up honestly. But strategic surrender creates a specific dynamic in a relationship: You can’t be a source of frame and direction if you’re perpetually surrendering your agency. The Nice Guy operating system—the need for external validation, the covert contracts, the inability to state my own needs directly—infected everything. I was asking her to respect a man who wouldn’t defend his own territory.

Temporal theft. This is the cruelest cost because it’s the only truly unrecoverable one. I cannot get back the years I spent in strategic surrender. I was 35, then 40, then 45, and the opportunities I didn’t pursue didn’t wait for me to overcome my fear of evaluation. Other men took them. Men who were willing to risk being found insufficient because they understood that the only way to become sufficient is to subject yourself to the test.

“I traded permanent capacity for temporary comfort.”

The cruel irony that became clear only in retrospect: The comfort I purchased was temporary. The relief of not having to defend a position lasted only until the next opportunity appeared and I had to surrender again. The psychological comfort was fleeting, contingent, always requiring renewal through fresh surrender.

The cost was permanent.

Kidney disease doesn’t reverse. Bankruptcy doesn’t un-happen. The years between 35 and 47 don’t reappear. The compounded financial returns I didn’t generate because I wouldn’t invest in my own capabilities—those are gone.

I traded permanent capacity for temporary comfort.

And I did it deliberately, systematically, with full knowledge of what I was doing—though I couldn’t admit that knowledge to myself at the time.

The spreadsheet doesn’t lie:

Financial: Hundreds of thousands in lost income, opportunity cost on investments not made, actual bankruptcy declared

Physical: Chronic disease that requires management for the rest of my life

Psychological: A decade of deepening shame and the specific torture of knowing you’re capable and choosing not to act

Relational: Dynamics that took years to repair once I started operating differently

Temporal: Twelve years in strategic surrender that I cannot reclaim

This is what “I can’t” actually costs when you deploy it as a lifestyle.

The fortress of defenselessness promised safety. It delivered a comprehensive, multi-domain catastrophe that I’m still digging out from.

The Compound Interest of Avoided Risk

There’s an economic principle that applies to psychology: compound interest.

When you invest money, it earns returns. Those returns earn their own returns. Over time, the compounding effect creates exponential growth.

The same principle works in reverse with avoided risk.

Every risk you don’t take, every opportunity you don’t pursue, every evaluation you don’t subject yourself to—these aren’t isolated events. They compound.

Here’s how:

When you avoid a risk at 35, you don’t just lose the outcome of that specific opportunity. You lose the skills you would have developed pursuing it. The relationships you would have built. The confidence you would have gained from succeeding (or the wisdom you would have gained from failing).

Those lost skills would have qualified you for bigger opportunities at 37. Those relationships would have opened doors at 40. That confidence would have let you pursue even more significant challenges at 42.

This is the compound interest of avoided risk: Every surrender makes the next surrender more likely, more costly, and harder to recover from.

I watched this play out in my own life with devastating clarity.

The promotion I didn’t pursue at 35 would have put me in position for a director-level role at 38. That director role would have given me the platform and credibility to make a strategic industry shift at 41. That shift would have positioned me for the kind of senior leadership role I’m only now, at 49, beginning to build toward.

The 14-year gap between where I am and where I could have been? That’s compound interest on avoided risk.

And it doesn’t just apply to career. It applies to every domain.

The health habits I didn’t build at 35 compounded into chronic disease at 45.

The financial discipline I didn’t develop at 37 compounded into bankruptcy at 44.

The relationship skills I didn’t practice in my 30s would have prevented conflicts and pain in my 40s.

Every avoided risk is a lost investment that would have compounded over time.

“Every avoided risk is a lost investment that would have compounded over time.”

The reverse is also true, and this is the hopeful part: Every risk you take now compounds forward.

The skills you build today qualify you for bigger opportunities tomorrow. The confidence you gain from this success enables you to pursue that challenge next year. The relationships you develop through authentic engagement open doors you can’t even see yet.

This is why starting matters more than perfect timing. This is why “good enough to begin” beats “perfect someday.” This is why taking the risk now, even if you’re not fully ready, is almost always the right strategic choice.

Because you’re not just playing for today’s outcome. You’re playing for the compound returns over the next decade.

I lost 14 years to the compound interest of avoided risk.

I’m not getting those years back.

But I can start the compounding in the other direction. Right now. Today.

And so can you.

The Sovereignty Insight: Having Something Worth Defending

The paradox that breaks the whole system: The path to peace isn’t having nothing to defend—it’s having something worth defending and the strength to defend it.

Strategic surrender promised relief from the burden of defense. What it delivered was the much heavier burden of knowing you surrendered.

The alternative—what I’m implementing now—is strategic ownership.

This is different from the stress-hustle. Strategic ownership isn’t frantic effort on safe tasks. It’s calm, directed force applied to high-leverage objectives that you’re willing to claim.

The shift feels like this:

Old OS: “I can’t make a mistake, so I won’t act until I have perfect clarity.”

New OS: “I will make strategic decisions based on imperfect information and own the outcomes.”

Old OS: “I can’t compete with those candidates, so I won’t apply.”

New OS: “I will enter the competition and let the evaluation happen.”

Old OS: “I can’t afford the risk of that investment.”

New OS: “I will calculate the risk, determine if it’s acceptable, and act accordingly.”

Old OS: Defend nothing, own nothing, risk nothing.

New OS: Choose what to defend, own those choices, manage the risk strategically.

The new operating system requires learning to conserve energy rather than dissipate it through stress-theater. It requires limiting stress to meaningful challenges rather than generating it through overthinking safe tasks. It requires using 80/20 thinking to identify leverage rather than pursuing comprehensive perfection.

Most importantly: It requires being willing to have skin in the game.

I’m implementing this now in concrete ways:

I take the step back before making decisions. Instead of diving into tactical execution, I ask: What are the second-order effects? What are the third-order effects? What am I actually optimizing for?

I conserve energy for high-leverage decisions rather than dissipating it on frantic motion.

I’m building the war chest I should have built years ago—because a man who controls capital has options, and options are agency.

I’m choosing where to apply force instead of applying it everywhere ineffectively.

The difference between this and strategic surrender is stark:

Strategic surrender: “I won’t risk this, so I’ll tell myself and everyone else I can’t.”

Strategic ownership: “I’m choosing not to pursue this because it’s not the highest-leverage use of resources right now.”

One is hiding from agency. The other is exercising it.

The Sovereignty Spectrum looks like this:

Strategic Surrender ← → Tactical Retreat ← → Strategic Ownership

No agency/No responsibility → Preserved agency → Full agency/Full responsibility

Comfortable/Impotent → Strategic/Flexible → Uncomfortable/Powerful

I lived on the left side of that spectrum for years. I’m moving right, and it’s the most uncomfortable thing I’ve ever done.

“Sovereignty is all or nothing. You can’t claim credit for success while outsourcing blame for failure.”

Because here’s what sovereignty actually means: You own everything in your world. The victories and the catastrophes. The brilliant calls and the unforced errors. The outcomes you intended and the consequences you didn’t foresee.

You can’t claim credit for success while outsourcing blame for failure. You can’t have agency only when things go well.

Sovereignty is all or nothing.

And that’s terrifying if you’ve spent years optimizing for defensibility.

But it’s also the only alternative to the slow death of strategic surrender.

I now have things worth defending:

Financial position I’m building

Professional territory I’m claiming

A vision for what I’m constructing over the next decade

Physical health I’m recovering

Relationships I’m showing up for honestly

Which means I can be evaluated. I can fail visibly. I can be found insufficient in some specific domain and have to own that.

And here’s what I’ve discovered: That vulnerability is the price of admission to an actual life.

The fortress of defenselessness was comfortable. It was also a tomb.

The Setup for Extreme Ownership

This article has been a diagnostic exercise. I’ve dissected the mechanism of strategic surrender, shown you its payoff structure, revealed its true cost.

I haven’t given you the solution.

That’s deliberate. Because the solution—Extreme Ownership—is the most uncomfortable operating system you’ll ever adopt. And you can’t implement it until you’ve seen strategic surrender for what it actually is.

The bridge between diagnosis and cure is this: Once you see the comfort of surrender for what it is—a psychological con that purchases temporary relief at the cost of your entire future—you cannot unsee it.

You’ll hear “I won’t” underneath every “I can’t.”

You’ll recognize the theater of frantic effort for the avoidance mechanism it is.

You’ll feel the difference in your body between genuine limitation and strategic retreat.

And you’ll be faced with a choice.

You can rebuild the story. Go back to the comfortable lies. Resume the performance. There’s no external force preventing this. Strategic surrender is always available.

Or you can accept the uncomfortable truth: The only alternative to strategic surrender is total ownership.

Extreme Ownership—the doctrine developed by Jocko Willink and Leif Babin from their experience leading SEAL teams in combat—says this: You own everything in your world. Not just the things you control. Everything.

If your subordinate fails, you own that failure—you didn’t train them properly, didn’t give clear guidance, didn’t verify understanding.

If the mission parameters change, you own the adaptation—you don’t get to blame headquarters for the unexpected.

If you fail to achieve the objective, you own that—you don’t get to blame inadequate resources, insufficient support, bad luck.

You own it all.

This is the only operating system that makes strategic surrender impossible. Because Extreme Ownership doesn’t allow “I can’t” to exist as a category.

There’s only “I will” or “I won’t”—and if it’s “I won’t,” you own the choice and its consequences.

I’m implementing this doctrine now, in every domain. And it’s brutal.

Because I can’t blame my past circumstances for my current financial position—I own the decisions I made and didn’t make.

I can’t blame the bank for the promotions I didn’t get—I own my refusal to compete for them.

I can’t blame genetics or bad luck for my health crisis—I own the years of stress I generated and the self-care I deprioritized.

I can’t blame anyone or anything for the decade I spent in strategic surrender—I own every single day of it.

“That ownership is crushing. It’s also the only thing that makes change possible.”

That ownership is crushing. It’s also the only thing that makes change possible.

Because if it’s not your fault, you can’t fix it. If circumstances beyond your control created your situation, you’re stuck waiting for those circumstances to change.

But if you own it—all of it—then you can change it.

Extreme Ownership is the doctrine that replaces strategic surrender. It’s the alternative operating system.

And it requires you to have something worth defending, because you’re claiming ownership of your entire territory—the defended and the indefensible, the victories and the catastrophes, the capabilities and the gaps.

You’re saying: “This is mine. I own it. I’m responsible for it.”

And then you’re living with the consequences of that claim.

The Choice You’ve Always Had

Strategic surrender promised you safety. It delivered a cage.

You traded the risk of evaluated failure for the guarantee of invisible failure.

And now you know.

The fortress of defenselessness is comfortable. It’s also a form of death—slow, invisible, comfortable death.

You can stay there. Nothing external will force you to leave.

Or you can accept that the only path to an actual life—one with agency, sovereignty, the possibility of meaningful victory—requires you to claim territory and defend it.

To own your choices and their consequences.

To replace “I can’t” with the terrifying honesty of “I won’t” or the equally terrifying commitment of “I will.”

The choice is yours. It always has been.

That’s the uncomfortable truth you’ve been hiding from with strategic surrender.

And now that you see it clearly, the question is simple:

What are you going to do about it?

If you recognize the fortress of defenselessness in your own life and you’re ready to see what sovereignty actually costs, the next piece in this series will give you the alternative doctrine: Extreme Ownership.

But I’m warning you: once you accept full ownership, you can never go back to the comfort of “I can’t.”

The cage was comfortable. Freedom is terrifying.

Choose accordingly.